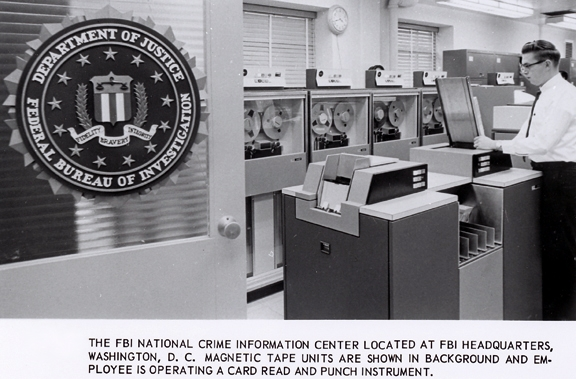

On January 27, 1967, law enforcement in the United States crossed a quiet but decisive threshold. There was no ceremony on courthouse steps, no flashing lights, no breaking news banner. Instead, the transformation happened behind terminals and phone lines, inside government buildings and command centers. On that day, the National Crime Information Center became operational.

With its launch, American policing began its shift from paper files and local memory to a national, interconnected system of shared intelligence. It was the beginning of modern information-driven law enforcement.

Before NCIC, officers relied on fragmented systems. Warrants were often local. Stolen vehicle records lived in filing cabinets. Identifying a suspect across state lines could take days or weeks, if it happened at all. An officer stopping a vehicle late at night might have no way of knowing whether the person behind the wheel was wanted three counties over or three states away.

NCIC changed that reality.

Operated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, NCIC was designed to do something revolutionary for its time: provide law enforcement agencies nationwide with immediate access to critical criminal justice information. Warrants, stolen vehicles, missing persons, firearms, and later protective orders and terrorist identifiers could now be queried in seconds.

For the first time, a patrol officer’s question did not end at the county line.

The early system was basic by today’s standards. Data traveled through dedicated terminals, and updates were slower than modern officers might recognize. But the concept was groundbreaking. NCIC established the principle that public safety improves when agencies trust one another with timely, accurate information.

That principle still defines policing today.

Over the decades, NCIC expanded in both scope and sophistication. What began as a limited database grew into a core component of nearly every law enforcement encounter in the country. Traffic stops, criminal investigations, missing person cases, and officer safety checks all became more informed because of NCIC returns.

For officers, that information can be lifesaving. A hit on a violent felony warrant. Confirmation that a vehicle was stolen hours earlier. An alert that the person being contacted has a history of armed resistance. NCIC does not replace training, judgment, or tactics, but it gives officers critical context before decisions are made.

That context matters on the street.

NCIC also reshaped investigations. Detectives gained the ability to connect cases across jurisdictions. Serial offenders who once exploited geographic gaps found those gaps narrowing. Patterns became visible. Leads developed faster. Cooperation became the norm rather than the exception.

Importantly, NCIC’s growth also brought accountability. Strict rules govern who can access the system, how information is entered, and how data is used. Agencies train personnel extensively, audit usage, and enforce compliance. The system’s power demands discipline, and law enforcement has worked for decades to balance access with responsibility.

Today, more than 18,000 agencies rely on NCIC. It processes millions of transactions daily. It integrates with state systems, mobile data terminals, and secure networks that officers now take for granted. Yet its core mission remains unchanged from that January day in 1967: get the right information to the right officer at the right time.

In South Carolina, NCIC is part of the daily rhythm of policing. Whether through local departments, sheriffs’ offices, or statewide coordination, officers depend on the system to enhance safety, efficiency, and effectiveness. It is woven into dispatch centers, patrol vehicles, and investigative units across the state.

Looking back, the launch of NCIC stands as one of the most consequential developments in American law enforcement history. It did not add a badge, a weapon, or a uniform. It added knowledge. And knowledge, in policing, often makes the difference between uncertainty and clarity, between danger and preparation.

January 27, 1967, reminds us that some of the most powerful advances in public safety are not dramatic. They are foundational. They work quietly, every day, in the background, ensuring that officers are not standing alone, but supported by a nationwide network committed to protecting the communities they serve.